The OS is always greener...

It's just one more chapter in the long and exquisitely awkward saga of Nokia and Symbian. From the outside I can't tell exactly what's going on at Nokia, and it's possible that Nokia itself doesn't know. It's a very large company, and various groups there can have conflicting agendas.

But I can't believe that there would be all of these repeated reports, leaks, and artfully-worded partial denials unless Nokia were de-emphasizing Symbian in the long run. The most prominent theory, which I believe based on things I hear through back channels, is that Nokia does indeed intend to move to Maemo at the high end. And, as we all know, in computing whatever's at the high end eventually ends up in the mainstream.

I'm sure Nokia has valid technical reasons for moving to another OS. Nokia has said that there are some things it wants to do with its smartphones that Symbian OS can't support. But still the change worries me. Nokia's biggest problem in the smartphone market isn't the OS it uses, it's the user experience and services layer in its smartphones. Moving to a new OS does almost nothing to fix that. It does force a lot of engineers to work on writing a lot of low-level infrastructure code that won't create visible value for users. It also forces Nokia to maintain two separate code bases, which will chew up even more engineers.

All of that investment could have gone into crafting some great solutions, the things that are the only way to pull customers away from Apple and RIM. At a minimum, it's a terrible shame that Nokia spent so much time and money on an OS that couldn't take it into the future.

(By the way, this focus on the OS doesn't apply only to Nokia. I hear a lot of buzz from operators and handset companies who believe that if they just pick the right OS they'll automatically end up with great smartphones. Android is the latest white knight for most of them, but of course Nokia's not going to depend on a technology from Google.)

There's an old joke in the tech industry about rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic. I don't think that applies to Nokia because they haven't hit an iceberg by any means. But I do have a mental picture of a sweet old lady who spends all her time every day cleaning the bathroom while the food is spoiling in the refrigerator.

Nokia and Microsoft, sittin' in a tree...

If you missed the press release (link), Nokia said that it's going to make Microsoft Silverlight available for all of its mobile platforms -- Series 40 (the low-end phone OS), S60 (the high-end OS), and its Maemo Internet tablet. (It's not clear if Silverlight will be bundled or just offered as a download.) Silverlight is a web app graphics and interface layer, intended to displace Adobe Flash.

The announcement was shocking for several reasons:

--Up until now, Nokia and Adobe had worked together closely. Nokia is one of the few companies paying to bundle Flash on its phones, and Nokia had featured Adobe prominently at some of its developer events in Silicon Valley. So the announcement I was expecting was that Nokia would bundle Air, the next evolution of Flash, rather than its competitor.

--Nokia has generally treated Microsoft as the spawn of the devil. The whole Symbian OS consortium was designed primarily as a way to prevent Microsoft from getting a controlling role in mobile software. Now Nokia gives Microsoft's software layer a huge boost?

--Although Microsoft had hinted vaguely about taking Silverlight mobile, it had given no definite plans at all. So this is a huge step forward for Silverlight.

--Just a few weeks ago, Nokia bought TrollTech and announced that its software was going to unify development across Series 40 and S60. Now Nokia endorses Silverlight, which will also run across Series 40 and S60. Which one are developers supposed to focus on?

What in the world is going on?

I don't know. Nobody from Nokia has explained it to me, so I have to read between the lines. Nokia says in the press release: "Nokia aims to support market leading and content rich internet application environments and to embrace and encourage open innovation. By working with Microsoft, we are creating terrific opportunities and additional choices for the development community." Okay, so I guess what they're saying is that they want to support every platform and development option out there. Presumably the benefit to them is that they can claim their phones support more software than anyone else.

I doubt that's the only motivation, though. By supporting numerous platforms, Nokia reduces the possibility that any one of them can dominate the market and push around Nokia. It also lets Nokia play the sides off against one another. I'm sure the threat of embracing Air made Microsoft give Nokia a very good deal on Silverlight, and no doubt Nokia will now use its Microsoft relationship to get business concessions from Adobe (assuming that Nokia still plans to work with Adobe at all; that's not entirely clear).

Anyway, I can sort of see how this all works for Nokia strategically, although it feels like Nokia is trying too hard to be clever. I'm not as clear on the benefits of all this for mobile developers and users. As was covered in last week's post on mobile apps (link), many developers view the proliferation of platforms as a problem, not a benefit. Microsoft itself said in the Nokia press release:

"We want to make sure developers and designers don't have to constantly recreate the wheel and build different versions of applications and services for multiple operating systems, browsers and platforms."

That's a pretty danged funny quote coming from a company that now offers at least four mobile platforms (two versions of Windows Mobile, Silverlight, Tablet PC, and does .Net CF count as a fifth?), in a press release from a company that apparently wants to support every platform available. If you really think platform confusion is a problem, guys, look in a mirror.

For users, the benefit of all this deal-making is unclear. We're stumbling into a world where you'll need to know details of which platforms are loaded on a particular phone in order to know which apps it can run. I can't think of a better way to discourage use of mobile applications.

Google, the OS company

The fact that Google's recently-announced OS products are aimed at mobile devices and social networking sites is interesting, and I'll talk about the impact of that below. But it's secondary. I think the big, really important change is that Google has now jumped with both feet into the middle of the operating system world. That potentially has huge implications for the industry.

The impact will depend a lot on how Google follows up. If it pours substantial energy and resources into its OS offerings, it will be extremely bad news for Microsoft and other companies trying to charge money for their own platforms. On the other hand, if Google doesn't make a serious long-term commitment, it will embarrass itself deeply. This isn't like launching a new web application -- an OS has to be complete, and it has to work properly in version 1, or there won't be a version 2.

What they announced

It's kind of ironic. For years after Google became a prominent web company, people speculated about whether or when it would create its own OS. The logic was that Microsoft has its own OS, and Google was challenging Microsoft, so Google would create its own OS too. But then as the years went by and it didn't happen, people moved on to other subjects. The speculation died out. But one of my rules about the tech industry is that "obvious" things happen only after everyone in the industry has written them off. So I guess Google was due.

The company has been creeping toward the OS space for a while. Google Gadgets is an API to create small applications that run in web pages, and Google Gears is code that lets web apps run offline, making it easier for them to challenge desktop applications. But they were both relatively low-profile (or as low profile as anything Google ever does). But in the last couple of weeks, Google made two much more assertive announcements:

--OpenSocial is an effort to create a shared platform for applications that can be embedded within social websites (link).

--The Open Handset Alliance is an effort to create a shared platform powering mobile devices (link).

Although they're aimed at very different parts of the industry, they're both efforts to create a standard platform where there was fragmentation; and they're both alliances of numerous companies, with Google providing most of the code and the marketing glue. I think there's a recurring theme here.

Details on the Open Handset Alliance

Open Social was covered very heavily when it was announced a couple of weeks ago, so I won't recap it all here. If you want more details, Marc Andreessen did an enthusiastic commentary about it on his weblog (link).

The OHA announcement was today, and I want to call out some highlights:

--It's built around a Linux implementation called Android. Android will be free of charge and open source, licensed under terms that allow companies to use it in products without contributing back any of their own code to the public. This will probably annoy a lot of open source fans, but it's important for adoption of the OS, as many companies thinking about working with Linux worry that they will accidentally obligate themselves to give away their own source code.

--Google is creating a suite of applications that will be bundled with Android, but they can be replaced freely by companies that want to bundle other apps, according to Michael Gartenberg (link). There is a lot of speculation, though, that if you bundle the Google apps you'll get a subsidy from Google. The folks over at Skydeck estimate the subsidy could be about $50 per device (link). That might not sound like huge money to you and me, but keep in mind that mobile phone companies routinely turn backflips to squeeze 25 cents out of the cost of a phone. When you sell millions of phones a year, it adds up.

--A huge list of companies participated in the announcement. That's not as impressive as it sounds; when you have a well-known brand, a lot of companies will do a joint press release with you just for the publicity value. But a few stood out:

Hardware vendors. Samsung, Motorola, LG, and HTC all endorsed the OS. HTC and LG gave particularly enthusiastic quotes. The first three companies have all been playing with Linux for some time, so I wasn't surprised. But HTC is another matter -- it is the most innovative Windows Mobile licensee, and Microsoft must be very disturbed to see it blowing kisses at Google.

(A side comment on Motorola: For a company that said it wanted to consolidate down on a small number of platforms, Motorola is behaving strangely -- it jumped all over Symbian a couple of weeks ago, and now is supporting Android as well. I think it has now endorsed more mobile operating systems than any other handset vendor.)

Operators. Participants in the announcement included NTT DoCoMo (a long-time Linux lover), KDDI, China Mobile, T-Mobile, Telecom Italia, Telefonica, and Sprint. That's a very nice geographic spread, and ensures enough operator interest to make the handset vendors invest.

--Google claims all Android applications will have the same level of access to data on the phone. That's pretty interesting -- most smartphone platforms have been moving toward a multiple-level approach in which you need more rigorous security certification in order to access some features of the phone. I'll be interested to see how the security model on Android works.

--We'll get technical information on the OS November 12, and the first phones based on Android should ship in the second half of 2008.

--Although Android's first focus is mobile phones, the New York Times reports that it can be used in other consumer devices as well (link).

What it means to the mobile industry

It all depends on the quality of Google's work and the depth of its commitment. If Android has technical or performance problems, it could sink like a stone. If it doesn't have enough drivers or has poor technical support, the handset vendors will avoid it. If the developers can't create good applications, users won't want it. This is a very different business for Google -- handset vendors and operators will not tolerate the sloppy, indifferent technical support that Google provides for its consumer web apps.

If, on the other hand, Google's platform really works and the company invests in it, I think it could have some very important impacts.

Impact on Windows Mobile: Ugliness. The handset companies endorsing Android are also Microsoft's most prominent mobile licensees. I doubt any of them are planning to completely abandon Microsoft (they don't want to be captive to any single OS vendor), but any effort they put into Android is effort that doesn't go into Windows Mobile. So this is ominous.

The whole mobile thing just hasn't worked out the way Microsoft planned. First it couldn't get the big handset brands to license its software, so it focused on signing phone clone vendors in Asia, thinking it could use them to pull down the big guys. But Nokia and the other big brands used their volume and manufacturing skill to beat the daylights out of the small cloners.

Now Google is coming after the market with an OS that's completely free, and may even be subsidized. This will put huge financial pressure on not just Windows Mobile, but all of Windows CE. Even if Microsoft can hold share, its prospects of ever making good money in the sub-PC space look increasingly remote.

Impact on Access: Ugly ugliness. How do you sell your own version of Linux when the world's biggest Internet company is giving one away? I don't know.

Impact on Symbian: Hard to judge. Symbian is the preferred OS of Nokia. As long as Nokia continues to use Symbian, it stays in business. The question is how much it'll grow. After years of painful effort, Symbian just managed to get increased endorsements from Motorola and Samsung. Now Google is messing with both of them. Japan has been a very important growth market for Symbian, now Android is endorsed by both DoCoMo and KDDI. All of that must feel very uncomfortable. If nothing else, it's likely to produce pressure on Symbian to lower its prices. And Symbian should be asking what happens if Android turns out to be everything Google promises -- a free OS that lets handset vendors create great phones easily. It's not fun competing against a free product that's been subsidized by one of the richest companies in the world (just ask Netscape).

Maybe if Symbian agrees to enable Google services on its platform it can get the same subsidies as Android does. It's worth asking. If not, maybe Symbian should be looking for other places where it can add value in the mobile ecosystem.

Impact on mobile developers: Potentially great. Mobile developers have suffered terribly from two things: They have to work through operators to get their applications to market, and they have to rewrite their applications dozens of times for different phones. If Android produces a single consistent Java environment for mobile applications, that would be a big win. And if it can open up the distribution channels for mobile apps, that would be great as well. We don't have enough details to judge either outcome yet, and the app distribution one depends on business arrangements that may be outside Google's control.

Impact on Apple, RIM, and Palm: Probably none at all. A lot of the coverage of Android is positioning it as some sort of challenger to iPhone and RIM.

I don't buy it.

Apple, RIM, and Palm all make integrated systems in which the software and hardware are coordinated together to solve a user problem. Android, by contrast, is only an operating system. It's plumbing, not the whole house. Unless Google's handset licensees magically develop the ability to design for users -- a feat equivalent to a giraffe sprouting wings -- their products won't be any better as systems solutions than they are today. The OS hasn't been the thing holding them back, and changing OS won't alter the situation.

Android puts interesting financial pressure on Microsoft, but it doesn't directly solve any compelling user problems. If it eventually drives a great base of mobile applications, that might eventually be attractive to some users. But in that case the systems vendors could just add a copy of Google's application runtime (it's open source, they can grab it anytime they want). Or they could host their devices on Google's plumbing. Palm and RIM might both benefit if they could transfer engineers away from core OS and toward adding value that's visible to users.

Impact on the tech industry: This isn't just about mobile phones

I have no access to Google's internal thinking, but even if it sincerely believes it's only doing a mobile phone OS, I don't think it can or will stop there. Technology products often develop a momentum of their own, no matter what was intended at the start. The lines between the computing and mobile worlds are breaking down already, and if Google creates an attractive software platform that's free of charge, that platform will inevitably get sucked into other types of devices. I'm not saying that Android is going to end up in PCs, but if it's functional and well supported I think it could end up running on just about everything else that has a screen.

Besides, if you look across all of the recent Google announcements, I think it's clear that Google has a larger agenda: It wants to break down walled gardens, because they interfere with Google's ability to deliver its services. It has even developed a standard methodology for attacking them: Create a consortium so you don't look like a bully, and fund an "open" alternative to whatever is in the way. They are doing it to Facebook, and they're doing it to Windows Mobile. Google doesn't even have to make money from the consortium, as long as it clears the ground for its services to grow.

Take a lesson from evolutionary history. The most successful animals are not those that adapt to the environment; they are the ones that reshape the environment to match their needs. I think that's what Google is doing. It's going to use open source and alliances to suck the profitability out of anybody who creates a proprietary island that it can't target.

It'll be interesting to see if and how Google applies this principle to the upcoming frequency auction in the US.

Or to anyone else who gets in its way.

Why is Apple porting its browser to Windows? To take over the world, of course.

Jerry Yang is now in charge at Yahoo, which in my opinion means a lot because a founder is often much more willing to revisit old assumptions and make radical changes than is someone who came in after the fact. (I know the stereotype is that founders resist change, but I've found that the exact opposite is often true, especially if the founder is moving up after spending time lower in the management chain.)

Google bought Grand Central, which underlines their interest in providing client software for mobile phones. It's a significant change for Google because up to now they have focused mostly on providing mobile versions of their existing web apps, like Maps. Grand Central is different; it's a call management system that embeds Google deeply in the life of a mobile user. It implies a much tighter relationship between Google and the user than most other Google products, and it's not something that you can easily monetize through advertising -- which makes me wonder whether Google is planning to run it standalone or integrate it into something bigger.

But the strangest recent development was Apple's decision to port its Safari web browser to Windows.

It is not easy to port a browser to a new platform. There's a huge amount of programming involved -- to do the actual port, to debug it, and to maintain and upgrade the code as people identify small incompatibilities and ask for new features. I lived through PalmSource's effort to get a good browser for Palm OS, and talked with the Be veterans about their browser work. The quick summary: it's a huge pain in the butt.

What's Apple hoping to get? The engineers at Apple who are spending their time on Safari for Windows could be creating new features for the iPhone, or helping to finish the next version of Mac OS X. Although Apple is rich enough to hire a lot of engineers, the supply of really good ones is limited, so Apple's definitely paying a price to do the port. And for what? To get people to use an alternate browser, you have to give it away for free. So there's no immediate benefit to doing the port.

A lot of Apple enthusiast sites have asked what's going on, but I'm not persuaded by most of the answers they came up with. For example, a site called Apple Matters gave four possible motivations: for bragging rights, to show Windows users what it's like to use a Mac, to give iPhone website developers a tool to test their sites, and to get revenue from search referrals to Yahoo and Google (link).

Apple Matters seems like a very good site, and to give them credit, even they were skeptical about some of the possible explanations. None of them work for me. Apple doesn't need more bragging rights, a browser is a very awkward way to show off the Mac UI, iPhone developers can buy an iPhone to test their sites, and the search referral fees from Yahoo and Google can't be all that big or everyone would be writing browsers.

I think the motivation runs deeper. It turns out that Apple didn't just port the browser to Windows; it ported the browser, the underlying Web rendering engine, and the Mac OS X programming frameworks that the browser relies on. In other words, Apple ported an entire OS layer onto Windows, and the browser is riding on top of that (link).

Now that's interesting. Apple is backing into the cross-platform OS layer business. Maybe the OS layer is just a convenient way to do the browser port. Or maybe the browser is just a trojan horse to get the OS layer on a lot more systems.

Add to this situation Apple's other recent strange announcement -- that it's "enabling" iPhone applications development by supporting Ajax web software on the iPhone. The problem with Ajax/Web2 applications is that they rely on a constant network connection in order to work. They're just thin clients to a server on the Web. Considering the iPhone's lack of true 3G connection speed, and AT&T/Cingular's well-documented data coverage limitations, Ajax-style development is about the worst thing you could do on the iPhone. What the developers wanted was the ability to create native Mac OS X applications, and Apple blew them off.

Why piss off the developers, and why put such a huge handicap on people supporting your critical new product?

Maybe the iPhone is so screwed up internally that it can't support third party apps. Sure, and maybe Apple wants to port Safari to Windows just for ego.

If you want a single idea that explains both actions, it's this: Apple realizes that in the long term, the development platform that matters is not the OS on the hardware, but the software layer that the web apps run on (I believe that; you can read more here). Apple realizes that this layer will eventually become good enough to displace native personal computer apps. Web apps then become both an opportunity and a challenge for Apple. The opportunity is that they're a way to take down Microsoft. The challenge is that the same process that obsoletes Windows obsoletes other PC operating systems, including Mac OS.

This makes it vital for Apple to create its own Web apps layer, so it can control its own destiny and increase its power. That goal would be so important that Apple would be willing to handicap iPhone apps development in the short term in order to make developers focus on the web apps platform in the long term.

If that's Apple's thinking, then the next thing to watch for will be Apple gradually adding more features to its OS layer, in the guise of browser APIs and feature enhancements. Those features will be deployed at the same time on the Mac, the iPhone, and Windows Safari. And Apple will start evangelizing web app developers to use them.

The war to come. This could set up a brutal competition in software layers, between Adobe Apollo, Microsoft Silverlight, Sun's revised Java, Firefox's platform, and Apple. Google fits in there somewhere as well, but it's not clear if they'll try to create their own platform or work with several other players.

I think this is where the most interesting action's going to be in applications development in the next few years. Stay tuned.

The people who say Web 2.0 apps are garbage are completely right -- and utterly wrong

But that's not the whole story. When you step back from the individual trees and look at the forest, I think the things happening in web apps today are really and truly revolutionary. If anything, the changes are a lot more profound than most people realize. And I believe they're just getting started.

As I've mentioned in other posts, the Web isn't just a place for publishing content, it's also rapidly maturing as a platform for developing new software applications. (Quick definition: in Silicon Valley-speak, a platform is a technology on top of which people build other products. Windows is a platform, as is Linux.) To me, the most important thing about the Web 2.0 sites is that they blur the distinctions between web pages and applications. Most of them don't just present information, they also let you create or manipulate it, as would a software program on your PC. Google Maps isn't just a website, it's an application for searching maps. Ten years ago, you would have bought it on a CD-ROM and installed it on your PC.

Participating in the blossoming of a new software platform is one of the most exciting things you can do in the tech industry. I've been lucky enough to be in on it twice now (Macintosh and Palm OS), and it's great because you get to work with a lot of smart developers who produce cool and surprising stuff. The excitement is infectious (thus the hype about Web 2.0).

But despite the attention people put on platforms, the way a new platform develops is not well understood in the tech industry. I think that's why people are getting confused about the fate of the Web 2.0 companies.

For example, here's a quiz -- do you know what the following names have in common? (No fair using Wikipedia; you have to do this on your own.)

Paladin

Ann Arbor

Cricket

Aldus

Silicon Beach

T/Maker

Living Videotext

If you said they're some of the most prominent early software developers* for the Macintosh, you're half right. The other thing they all have in common is that they're long gone -- out of business, sold off, or just plain faded away. In fact, other than Adobe and Microsoft, virtually none of the prominent early Mac developers are still independent businesses.

The melancholy fact is that the vast majority of the early developers on any platform fail.

This carnage of the early developers happens because a new platform is by definition unexplored territory. The developers are basically trying a series of experiments to see which types of applications will sell well. Their hit rate is better than playing the lottery, which is why VCs are willing to fund them, but inevitably most of the experiments fail.

That doesn't make the platform a failure, and it doesn't mean the applications were a waste. The successful experiments make a ton of money, more than enough to make up for the failures. And even the applications that don't survive long term often teach us new concepts and business models.

I think the same sort of shakeout is going to happen with the current crop of web apps. Most of them will eventually die or get merged into other things. That's no big deal, it's how a platform works. What matters is what we're learning through this Darwinian process. And from that viewpoint, the Web applications world is shaping up as a stunning success.

I think the three most important developments we're seeing in the web apps world are:

1. We're learning how to create new communities rapidly and focus them on useful tasks.

2. The Web is spawning new forms of media at an unprecedented rate.

3. The Web apps platform is starting to evolve exponentially.

I know the Web apps world is overhyped, so I say this very carefully and very sincerely: I think any one of those trends would be enough to drive major changes in the tech industry and the world beyond. The fact that all three are happening at once is, to me, quite remarkable, and I think it's going to have an enormous effect on our lives in the next 20 years.

I want to talk about each one of the trends, and then wrap up with some comments on overall implications and what to watch for next. Unfortunately, this post started to get waaay too long, so I'm going to do it in stages. I'll start with communities in the next post.

In the meantime, here's an example of what happens when somebody starts to sense what's happening in web apps. This is from Mike Rowehl, a software developer in the mobile phone industry, commenting on what he saw at the 3GSM telephony conference in February 2007:

"I was forced to realize that the mobile world won’t end up changing the online world like I had assumed it would. It really looks like the innovation is going to flow the other way around. People who are already working in mobile have had all semblance of initiative and innovation beaten out of them. You can lay a new business model down in front of them and explain in detail how it works, and generally they aren’t able to grasp it unless it looks enough like something they already know. However, people coming from the online world and looking to expand into mobile generally are accustomed to a shifting environment and taking in new opportunities and integrating them into their mental framework.... The stage should be set for mobile to completely subsume the online world. But instead it’s the people from the online world staggering out into the sun and realizing there’s no one trying to grab the potential of the new medium and just picking up the pieces waiting for them."

Mike, you ain't seen nothing yet.

__________

*Here's a key to those old Mac developers. Even though the firms and most of the products disappeared, many of the product concepts, and the people, went on to great success. I expect the same thing to happen in web apps.

Cricket Software. Creator of a series of Mac graphics programs, including Cricket Graph, Cricket Draw, and Cricket Presents (one of the first presentation programs -- a category that Apple called "Desktop Presentations" in an effort to duplicate the desktop publishing phenomenon). Cricket was run by Jim Rafferty, a really nice guy who went on to found and co-found several other companies. I couldn't figure out what he's doing now; please post a comment if you know.

Paladin Software was creator of Crunch, a Macintosh spreadsheet program that went head to head with Excel and lost. I thought Crunch was much easier to use than Excel, with an innovative icon bar for commonly used functions. Microsoft kind of borrowed that feature later (check the screenshots here).

Aldus. Creator of PageMaker. Adobe gets the credit today for driving desktop publishing, but PageMaker was the greatest page layout product of its time, easy to use and very powerful. I believe it was the program most responsible for making the Mac a commercial success. Aldus was run by Paul Brainerd, an extremely nice guy who told his company to respond to requests from small software developers like me. Thanks, Paul! He's now a philanthropist.

Ann Arbor Softworks developed FullWrite, which claimed to be the first fully WYSIWYG word processor, and which was also one of the most notoriously prolonged instances of vaporware in computing history.

T/Maker was one of the early developers of Macintosh desktop publishing software. Heidi Roizen, CEO of the company during its Macintosh days, was a deeply respected Macintosh software entrepreneur, and later became VP of the developer relations team at Apple. She's now a venture capitalist.

Living Videotext. Produced the ThinkTank and More outliners. Run by a guy named Dave Winer. And yeah, he was just as outspoken back then.

Silicon Beach Software. Mention "Silicon Beach" to an old-time Mac user and they'll probably just sigh. The company was responsible for many of the most creative Mac programs of its time, including a game called Dark Castle and SuperCard, an early hypertext development environment that extended Apple's HyperCard in wonderful ways. Some Silicon Beach veterans later founded Back to the Beach Software, whose name is a tribute to Silicon Beach.

Is Vista the end of Windows?

You can read the rest of the article here.At the end of 2006, Gartner Group predicted that Vista would be the last major release of Windows, with future updates being delivered on the fly, in modular format. "The era of monolithic deployments of software releases is nearing an end," Gartner said. "Microsoft will be a visible player in this movement and the result will be more flexible updates to Windows and a new focus on quality overall."

The annual predictions from the major analysis companies are like hors d'oeuvres at a drunken New Year’s party -- quickly consumed, and generally forgotten the next day. Their role is to generate publicity (that's why they are given away for free). But this prediction is worth thinking about because if true, it would have a profound impact on the computing industry...

________

By the way, I wanted to thank TomSoft for including my post on the Impact of the iPhone in the latest Carnival of the Mobilists, a weekly collection of mobile-related commentary.

We need a new mobile platform. Sort of.

Two weeks ago, I asked why mobile application sales are dropping. A great discussion followed, with many different perspectives (if you haven't read the comments, I encourage you to check them out).

To me, one of the most striking comments was the one no one made – nobody came back and said, "you're wrong, sales are actually going well." I think we have a consensus that there's something wrong with sales of sophisticated mobile data apps – native apps that are more than just games or ringtones.

There are two schools of thought on why app sales are down. One perspective is that the market was a mirage in the first place – most people don't care that much about mobile apps, and to the extent that they do, mobile browsing is a good substitute. I think this perspective is growing quickly among industry insiders, and even someone from Microsoft largely seconded it.

Another interesting example of this view is the weblog i-Mode Business Strategy, which tracks adoption of i-Mode data services. It's carrying a lot of quotes from operators and others saying that a mobile device should be focused on a single purpose, and the whole idea of deploying a lot of different apps or functions is low-value.

"All i-mode applications are in fact secondary, the primary being the voice. The secondary applications typically struggle through out their life cycles for the lack of focus and synergy."

The other perspective is that a diverse market for mobile data exists, but we just haven't tackled it correctly yet. For example, Bob Russell at Mobile Read wrote a very kind commentary on my post, but also strongly encouraged people not to panic and give up on the future of mobile data. Several of the other replies to my post echoed that theme.

I'm somewhere in the middle. As I've written before, I believe that a mobile device has to solve a compelling problem before people will buy it. Solving fifteen problems is too hard to market, so there needs to be one flagship function or usage that gets a device sold in the first place. In this respect, I think the "mobile device = appliance" folks are right.

But once the user gets a mobile device, I think many customers will allow it to blossom into more usages – if that blossoming process is handled properly. That's where I think the mobile data world fails today, and that's what I think we need to fix.

The role of mobile data

When I started work at Palm in 1999, I was already using a handheld to track my calendar and contacts, but not much else. I was lucky enough to get a cubicle in the middle of the developer relations team, who taught me all about the third party apps that were just then starting to take off for the platform.

The variety was so huge that I'd spend hours browsing around on PalmGear, picking out new things to download. Many of the applications turned out to be things I tried once and never touched again, but a few filled meaningful roles in my life and I came to depend on them.

There was my buddy Convert-It, which converts between English and Metric measurements (a must for any competitive analyst based in the US).

Tide Tool tells me when it's a good time to go tide pooling at the beach.

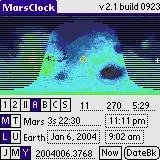

Mars Clock lets me track the time of day on Mars for the Mars Rovers. (Why does that one matter? Because if you're browsing the Mars Rover pictures that NASA posts on the Web every day, Mars Clock lets you convert between the Mars days that NASA lists and actual Earth days – so you can figure out when a picture was taken.)

This is a treasure chest

To me, the Palm Launcher became a treasure chest of useful little software gems, things that enhanced my life and made me happy. But I discovered that my gem collection was different from everyone else's. Tide Tool didn't matter to most people, and Mars Clock was interesting only to the fanatics who followed the photo stream from the Mars Rovers. Other people had their own favorite apps that I didn't care about.

Even among the Palm enthusiasts, there was never a single "killer" application everybody used. Instead, everyone had a different set of personal killer applications that met their own individual needs. Each person was a vertical market of one, the exact opposite of a mass market.

I discovered that when I was talking with potential customers or the press, I could hook almost anyone on Palm if I had fifteen minutes to show them the range of software available. But you can't spend a quarter hour per customer on a product that sells for only a couple of hundred dollars – that's a great way to go broke slowly. So we started to look for mass market ways to have that conversation.

At one point Palm planned an extensive TV advertising campaign for the range of applications, called "The Perfect Day." The first commercial was already finished when the tech bubble burst and Palm's stock value collapsed. The company decided to cut expenses, and the commercials were the first thing to go. The video was shown at a few trade shows, and that was all. (I tried to find a copy of the commercial online, but couldn't. If you know where to see it, please post a link.)

Later, when I was at PalmSource, we didn't have nearly enough money to do TV ads, so we tried to use the Web to spread the story. The result was something called the Expert Guides, a set of about 50 volunteer-written guides to applications for Palm OS. I'm more satisfied by these guides than I am by just about anything else I was involved in at Palm.

If you want to understand the power of mobile data software, and what it can mean to a person's life, browse some of the Guides. The ones on personal health, aviation, and professional medicine are especially impressive, but you can also find quirky things like cigar and liquor software, scuba diving software, and software for various religions.

In addition to creating the Guides, we ran a couple of contests soliciting first person usage stories from users. They were big successes, generating several thousand stories. They ranged from comical to heart-wrenching – people using handhelds to overcome disabilities or start new careers. Almost every story featured different apps. One story I remember in particular was reprinted in the Aviation expert guide:

"I'm a Mission Pilot with the Civil Air Patrol, the auxiliary of the U.S. Air Force. Installed on my Palm Powered device (a Tungsten T now, but over the past six years I've owned an i705, Palm Vx, Palm IIIx and Pilot Professional) are several aviation application including the Airplane Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA) airport directory. It contains virtually all information about thousands of airports across the US. On a January 11 night flight over northeastern Oklahoma, we heard a pilot call over the radio that he was having difficulty finding his destination airport in the darkness. He was alone and his charts were inadequate, out of date or missing. While my crewmember dug through his flight bag of charts, maps, directories and other guides, I pulled my Palm i705 out of my flight suit, turned on its internal light, opened the AOPA eDirectory and found information on the airport that this pilot was flying to. Within 60 seconds, my radio call advised the lost pilot of the airport's location, frequencies, hours of operation and instructions for turning on runway lights and rotating beacon from his aircraft. And my hands never left the flight controls. Is the Palm a great device? You bet. Is there a wide variety of software for use on it? An unbelievable amount. Is it convenient to use, even while flying an airplane? Absolutely. A lifesaver? The other pilot would certainly say so. And it's never farther away than the front pocket of my flight suit."

We had a database with several thousand of those stories. We never figured out what to do with them, other than list a few of the best ones in the Guides.

Based on all this interaction with customers, I an utterly convinced that mobile data, and all the myriad applications associated with it, will eventually be a very common, well-loved part of the lives of huge numbers of people around the world. This stuff is just too useful once you really dig into it.

I'm also convinced that conventional marketing won't make mobile data happen, because the compelling thing about mobile data isn't the total number of applications – it's the individual discovery of an application that does something critical just for you. We have to find a way to explain mobile data differently to every individual person.

After you think about it for a while, the right place – maybe the only place – to explain this is on the device itself. I think the right way to do it would be something like this:

When the user first gets started, the device asks the user a few questions about their work and interests. Based on the user's responses, the device suggests the installation of appropriate software. So, for example, if the user is a doctor and a boy scout troop leader, the device suggests a selection of medical software, and a boy scout troop management program (yes, there's an Expert Guide on that, listing about 70 relevant applications, including knot-tying instructional software -- something critical for a Scout). If the user agrees, these are downloaded to the device, and the user's wireless account is automatically charged for them. If the user doesn't agree, the device makes it easy to come back and buy the software later.

By customizing and automating the whole application shopping process, we make it easy for people to discover what they can do and get used to the idea of using their device for more than one purpose.

I think this integrated discovery and install process is the key to making mobile data take off.

Why hasn't it happened already?

If the right thing to do is so obvious, why hasn't some mobile OS company done it already? I spent the last seven years wondering about that question, and never got a satisfactory answer.

But I get it now.

Making real, personalized mobile data succeed isn't in the critical interest of any of the powers in the mobile design chain.

Hardware vendors focus on the lead solution that's built into their device, because that's what drives the hardware sale. So, for example, Palm has a strong incentive to spend all its time making e-mail on the Treo work great.

The OS vendors focus on the needs of the people who control their sales. That means supporting the feature requirements of the mobile operators, because they're the ones who decide if devices with a particular OS will be offered to users.

To an OS company, the operators are a feature requirements black hole, an "endless aching need" in the words of Bette Midler and Amanda McBroom. There's always one more feature they want implemented, or one more deal you can close if you just respond to a request. These opportunities expand to consume all available engineering resources, no matter how many engineers your company has.

I finally understood this a couple of months ago when I was talking with a former Palm employee who had moved on to one of the biggest mobile-related companies – a firm so huge that you'd assume they have enough engineers to do anything. We were talking about flaws in the user interface of a new product the company had released.

"Hey," I said to my friend, "You're on the inside now. Why don't you just call the product manager and explain to him what's wrong?"

"I did," my friend replied. "But the product manager said all the engineers are busy answering operator requests, and there's no one left to work on user features."

"There's no one left to work on user features." If mobile data fails, you can carve that on the tombstone.

We need a new platform – sort of

If we can't count on the OS companies to make mobile data work, then the obvious answer is to get away from the OS companies. Separate applications discovery, purchase, and compatibility from the underlying OS. Let the OS company serve the needs of the hardware companies and operators, while this new software layer serves developers and users.

What we need isn't a new OS, we need a new software layer on top of the OS.

I think that software layer should include:

--The APIs needed to run the applications, consistent across all devices so developers can write once and run anywhere (think of this as Java done right). That creates the largest possible market, encouraging the creation of the focused vertical applications that drive mobile data adoption.

--The software discovery and sales experience. The whole chain from learning to purchase to billing to installation should be built in, to make it effortlessly easy for people to try and install new mobile apps.

--The billing system needs to be managed carefully. The right thing is take a sustainable, restrained cut of developers' revenue and grow along with them. Many online mobile software stores take an enormous cut of the developer's revenue. That doesn't cultivate a developer community, it's more like running a McCormick harvester across it – you bring in an impressive harvest for a little while, but in your wake you leave an empty field of stubble.

--An open garden. Any developer should be free to add an application to the store. Real mobile data is so diverse that no entity on this earth is capable of determining in advance what people will want. Rather than trying to pick winners, the platform vendor should take a uniform cut from everyone and let Charles Darwin choose the winners. Better yet, put in a user rating system to help the best apps rise to the top.

--Sandboxing. Because anyone can publish an app, the software layer should be thoroughly sandboxed so that a rogue app can't mess with the phone network. This is much easier to do when the layer is built on top of the OS rather than within it.

--The layer should include enough of the user interface so that developers don't have to rewrite their apps for every different device.

Which companies could make it happen?

No one's putting together the whole offering yet, but there are some promising possibilities...

Adobe Apollo. Adobe says it's creating a software layer that will run on top of both PCs and mobile devices. Adobe has enough financial resources to make the necessary investments, and operators are anxious enough to get Flash content that they might agree to bundle Adobe's software.

But to succeed, Adobe would need to give away Apollo. Today the company is charging for Flash in the mobile world, which will limit its deployment and prevent the creation of a standard. Also, Adobe hasn't shown any signs of including application discovery or purchase in Apollo.

Microsoft WPF. Microsoft is working on a software layer that's conceptually similar to Apollo, called Windows Presentation Foundation. Like Apollo, it's not clear if WPF will include the software discovery and purchase experience. Also, Microsoft is holding some features out of the cross-platform version of WPF in order to prevent it from cannibalizing native Windows sales. That's a very difficult line to walk.

Nokia S60. Nokia's S60 software is closely tied to Symbian, but the company could theoretically separate it and offer it as a layer. I have no idea if that has been considered, or how hard it would be to implement. Nokia has been making some efforts at improving the app discovery experience, including the recent announcement of the "Nokia Content Discoverer," one of the most awkwardly-named software products I've heard of in the last five years. I like the idea, though – it's supposed to help people find content and apps. I haven't been able to find any pictures or video of the product in action. If you're aware of any, please post a link in the comments below.

Nokia's other handicap is that it's very closely tied to the operators. It would have to hive off resources to support the apps platform separately from operator influence.

StyleTap. This small Canadian company has created a Palm OS emulator and is selling it for use on Windows Mobile devices. So you can run most Palm OS apps on Windows Mobile. There's no software discovery element, but it is a nice software layer, and could be evolved into a layer for all mobile devices. Unfortunately, StyleTap is charging $30 a pop for the emulator. If they wanted to become the mobile software layer of the future, they'd need to give it away and make money through app sales. I doubt a company of their size can afford to do that.

Brew. Qualcomm's Brew has one of the nicest software downloading and billing infrastructures I've seen, and includes a set of APIs. So it's a full software layer. Its two problems are first that it's made by Qualcomm, a company that already holds – and charges for – many fundamental mobile patents. The last thing mobile companies want to do is give Qualcomm more control over their lives. The second problem is that Brew is set up as a series of closed gardens. The operators choose which apps to offer, and there's no discovery experience that I'm aware of. So I'd classify Brew as great technology hamstrung by a completely wrongheaded business model.

Savaje. This company has gone through a full cycle of being unknown, hyped into extreme prominence, and then dropped back into obscurity. What they're trying to do is fix Java, by making it consistent across devices, efficient, and wrapping a better business and technical infrastructure around it. The question about Savaje has always been whether or not they can deliver. I'm not close enough to them to judge that, but if they get their act together they could be a promising option.

I know I've skipped a lot of other candidates, but hopefully you get the idea (if I missed your favorite, feel free to post a comment about them). There are a lot of companies trying to make various sorts of software layers, but most of them are focusing on the APIs and technologies, the traditional control point in the PC world. That's nice, but what's really needed is a new business layer and infrastructure, not just another set of APIs. I think the first company that realizes this will be the one that drives the blossoming of mobile data.

I hope it'll happen soon.

Popular Posts

- 199 iphone wall paper

- Scanbuy Announces Addition to Its Board of Directors

- Millions of Names Available for .Co Open Registration

- YouTube Mobile 3G Enhancements & Java Beta Launchd.

- What a wonderful Second Life!

- Google Wave: First impressions

- Nokia N8 + Bluetooth Keyboard + Mouse

- Developers unhappy over Oracle Android suit

- Caribou Coffee to Use Cellfire for Mobile Coupon Offer

- Catching up: 8 random things about me